7th Florida Volunteer Infantry

Company K

Key West Avengers

In November 1861, the state of Florida issued a call for coast guard companies to be formed. One such company, commanded by Captain Henry Mulrenan, was sworn into service to the State of Florida on December 13, 1861. They would be stationed in and around the Tampa Bay Area. As a Coast Guard Company, Mulrenan’s company was responsible for watching the coastline for enemy activity. To fulfill their duties, they frequently utilized small armed sloops. Eventually, they adopted the moniker, Key West Avengers. They probably did not anticipate being sent out of Florida to fight at any point.

Forming the 7th Florida

On February 2, 1862, the War Department of the newly formed Confederate States Government issued a call for troops, with a quota for each state to fulfill. For Florida, this meant raising over two regiments of infantry. Having already sent four infantry regiments (1st – 4th Fl), this new call for troops resulted in the formation of the 5th, 6th, and 7th Florida Regiments.

The 7th Florida was mustered into service at Gainesville in April 1862. Initially the 7th composed of nine volunteer infantry companies, some of which had been in service for several months prior to the formation of the regiment. The Key West Avengers were added to complete the regiment and were designated Company K. Mulrenan was promoted to Major, and took over the assistant quartermaster duties for the regiment. His 2nd Lieutenant, Robert Smith, was promoted to Captain and took over command of the company. The company was then known as Smith’s Company.

Col. Madison Perry

As a small former coast guard company, the Key West Avengers grew in size when assigned to the infantry. The 7th Florida recruited much of its members from Alachua, Hillsborough, and Manatee Counties. Those who enlisted from Hillsborough and Manatee were often assigned to Company K, and by the time the regiment left Gainesville, company K numbered approximately 100 men, at least 40 of which came from Manatee County, and the regiment around 1000. Their commanders were Col. Madison Perry, and Lt. Col. Robert Bullock.

Map of Confederate Heartland Campaign culminating at Perryville, Kentucky, October 8, 1862

Kentucky Campaign

While the regiment was garrisoned in Gainesville until early June, Company K was stationed in Tampa. Between early June and early July, the entire regiment was transferred to Columbus, Georgia, where they were assigned to the Army of East Tennessee, soon to be re-named the Army of Kentucky, under Major General E. Kirby Smith. The Army of Kentucky, with the 7th Florida included, partook in the Kentucky Campaign, also called the Confederate Heartland Offensive, alongside General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Mississippi. To prepare for this offensive, the 7th Florida was sent through Chattanooga to Knoxville, then on to the Cumberland Gap. The trip from Tampa to the Cumberland Gap began June 27, 1862, and they did not reach their destination until October. When

they weren’t traveling via train or steamship, they conducted over 730 miles of marching, much of which was done without tents and on half rations.

During the Kentucky Campaign, the Army of Kentucky opposed Union General Buell’s Army of the Ohio. The intention was to try to draw Kentucky, a boarder state, into the Confederacy. The Union sought to keep Kentucky, with Lincoln even expressing his belief in the state’s strategic advantage. After some minor success, the offensive was stopped at when General Bragg’s Army of Mississippi was defeated at Perryville on October 8, 1862. The 7th Florida was not involved in this battle.

The Union controlled Kentucky the remainder of the war, and the state never seceded. The campaign came at a loss for the Union, as well. They were forced to give up ground they had taken in Alabama and Tennessee, which would prove difficult to retake in the years to come. They also failed to peruse the fleeing confederate armies, allowing them to escape into Tennessee. General Buell was subsequently replaced with Major General William Rosecrans.

After the Kentucky Campaign, the Army of Kentucky and the Army of Mississippi were consolidated to form the Army of Tennessee, with General Bragg commanding. This was the 7th Florida’s assignment for the remainder of the war.

The 7th Florida fought under two different, distinctive regimental colors during the war. As was typical in the Confederate armies, their first flag was likely issued to them upon their joining of the Army of Kentucky in the summer of 1862. The design consisted of a white disk on a blue field with a white boarder. Regimental information would be painted in the white disk, and battle honors sometimes were painted on the blue field or white boarder. Though the flag was designed by General Buckner, it became known as the Hardee flag, and was the standard regimental colors for thr Army of Kentucky and later the Army of Tennessee until the spring of 1864.

7th Florida Regimental Colors, Hardee Pattern, ca. Summer 1862 - Spring 1864

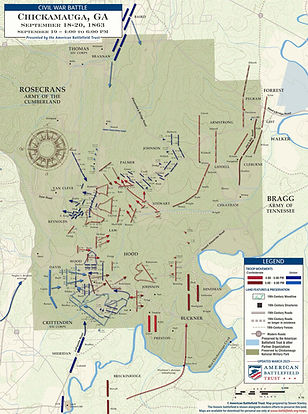

Chickamauga

Though they were not involved in heavy fighting during the Heartland Campaign, the 7th Florida did not have to wait long for their moment of glory. By September of 1863, Lincoln had pressured Rosecrans and his Army of the Mississippi into making an offensive towards Chattanooga. Chattanooga was a railroad town in the Tennessee River Valley. Located just north of the Georgia-Tennessee

Click to enlarge. These are just two of eleven maps of Chickamauga produced by the American Battlefield Trust. To see more, please visit their website.

border, Chattanooga was the gateway to the west, and was viewed by both sides as an important logistical hub and railroad junction. Rosecrans marched on Chattanooga from several different directions, and the Army of Tennessee, who was encamped in the city, met Rosecrans near a small creek called Chickamauga, southeast of Chattanooga, on September 18, 1863.

The 7th Florida played an important role in this particular battle. After a day of skirmishing along Chickamauga creek, the federals accomplished some success in delaying the rebel advance. At 11 pm that night, Confederate General James Longstreet arrived at 11 pm with his corps to reinforce Bragg.

The morning of September 19, Bragg split his forces into two wings, with Lt. General Polk assaulting Rosecrans’s lines along the right (northern portion) first, then Longstreet, now commanding the left wing of the confederate forces, assaulted the left (southern half) of the federal lines. It was this assault the 7th Florida fought in. It is important to clarify the 7th Florida was not part of Longstreet’s corps, but when Longstreet was assigned the left wing, it came with several divisions from the Army of Tennessee, including he 7th Florida.

Between 2:30 pm and 6 pm, the 7th Florida was engaged with federal forces under Barnes and Wilder, and after heavy fighting where they gained some ground, Sheridan’s arrival with his Union Cavalry forced the Trigg’s Brigade, the 7th included, back to the ground they had occupied that morning.

Unbeknownst to the 7th, the middle of the battlefield, Rosecrans made a severe tactical mistake. Believing a hole had opened in his lines, Rosecrans reinforced his left wing by moving troops from his center. This resulted in a hole opening in the middle of the Union line, right in front of Hood’s division. The confederate forces seized the opportunity, and flooded through the opening, separating the federal line. Rosecrans was forced to pull his troops back in order to reconnect the line.

The morning of September 20, Longstreet turned Rosecrans right flank and the union forces began to flee from the field. Seeing he had been defeated, Rosecrans left the XIV Corps under Gen. Goerge Thomas to cover the retreat of his army. Thomas firmly held a series of hills called Horseshoe Ridge, with Snodgrass Hill on the left flank. As the majority of the Union Army fled, Trigg’s Brigade was ordered to attack Horseshoe Ridge, and the 7th gallantly charged up Snodgrass Hill and captured 150 men and a flag from the defenders. The assault on Horseshoe ridge proved to be the breaking point, and the federal army retreated to Chattanooga. Thomas's defense of Horseshoe Ridge provided valuable time for Rosecrans to remove his army from the battle entact, and prevented a full rout of the Union forces. For this, Thomas would earn the nickname, "the Rock of Chickamauga."

The following is the official action report of Chickamauga written by the then colonel of the 7th Florida, Col. Robert Bullock:

“HDQRS. SEVENTH REGT. FLORIDA VOLUNTEERS,

Near Chattanooga, East Tenn., September 25, 1863.

CAPT.: I have the honor to report the following as the part taken by my regiment in the battle of Chickamauga, on the 19th and 20th instant.

Early on the morning of the 19th, my regiment was formed in line of battle on the north side of Chickamauga Creek, which line was at intervals advanced until the afternoon of the same day, when a charge was made upon a battery of the enemy stationed in a field in front of our line, from the destructive fire of which I was ordered to shelter my command behind the cover of woods immediately on my right, near which place my command bivouacked for the night in line of battle.

Col. Robert Bullock, Commanding 7th Florida Regiment, Volunteer Infantry

Early on the morning of the 20th, the line of battle was advanced as the enemy receded, until in the afternoon of the 20th the regiment was detached from the brigade with the First Regt. Florida Cavalry, and sent 1 1/2 mile back on the main road to intercept what was supposed to be a cavalry advance, from which place my command was moved in quick time to rejoin the brigade on the left of the hill in front of hospital, and then moved with the brigade upon a position of the enemy's in front and to the right, which resulted in the capture of about 150 prisoners, 1 stand of colors, and 12 Colt revolving rifles. Among the prisoners was Col. Carlton and Lieut.-Col. McLaw, regiment not remembered.

The conduct of the officers and men of my command was in the highest degree satisfactory.

I am happy to report but few casualties in my command, nearly all of which occurred in the charge on the 19th, and of which a report has already been furnished.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

R. BULLOCK,

Col., Comdg. Seventh Florida Regt.

Capt. JAMES BENAGH,

Assistant Adjutant-Gen.”

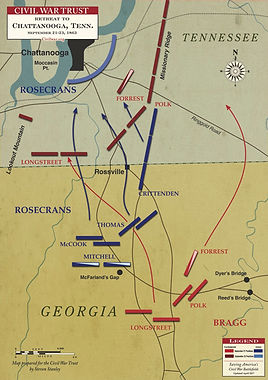

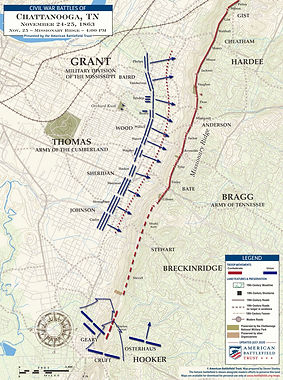

Chattanooga

Soon after their loss at Chickamauga, the Army of the Mississippi retreated to Chattanooga and created strong defensive works surrounding the small valley. Bragg, who stalled briefly after Chickamauga, not believing his enemy had left the field, arrived to find an already fortified the town. Instead of attacking, Bragg laid siege to Chattanooga. His lines stretched in a half circle, anchoring both of his flanks at the Tennessee River on

Click to enlarge. These are just two of several maps of Chattanooga produced by the American Battlefield Trust. To see more, please visit their website.

either side of the town. He commanded several heights, including Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, a steep rockyhill towering almost 1500 feet over the town below. North of the 400-yard-wide river spanned a rocky, hilly countryside with accessible roads and no river crossings into Chattanooga. Rosecrans was trapped.

Major General U. S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee was sent to relieve Rosecrans, along with Major General Hooker’s Corps from the Army of the Potomac. The now sizable Union forces sought to break the siege and move south into Georgia.

Prior to Chattanooga, Grant had been given command of the Military District of the Mississippi, which Tennessee was part of. Because of his failures at Chickamauga and now Chattanooga, Grant replaced Rosecrans with Major General George Thomas. As overall commander of the combined Union forces at Chattanooga, the responsibility of devising a plan to break the siege was left to him.

Captain Robert Smith, Commanding

7th Florida, Company K

Though the south had laid siege to the city, Grant was able to establish several routs in and out, allowing his troops to be reinforced and supplies delivered. On November 23, 1863, Grant began his attack on the fortified Confederate positions by ordering Hooker to assault Lookout Mountain, an incredibly daunting task. Hooker was aided by the recent transfer of Longstreet's corps back to the Virginia Theater, leaving lookout mountain lacking defenses required to hold against an attacking enemy. Hooker succeeded, sweeping the rebels off the mountain.

The next day, Grant ordered an attack on the Confederate defenses along Missionary Ridge. It was here the 7th Florida was entrenched near the center of the rebel line. The 7th suffered around 25% casualties in this fight, but Captain Smith, commanding Company K, was severely wounded. While the assault on Missionary Ridge ultimately did not succeed in pushing the confederates back, the assault on Bragg’s center did. With his left wing and center broken, Bragg was forced to retreat.

Atlanta Campaign

After the loss of Chattanooga, Bragg resigned and was replaced by General Joseph E. Johnston, who took command on December 27, 1863. Johnston was not President Davis' first choice to command. He initially offered the position to General Hardee, the senior corps commander in the army, but Hardee refused the promotion. After considering Generals Beauregard and Lee, Davis eventually chose Johnston, whom he had a tumultuous relationship with, at best.

The following spring, Johnston changed the official standard regimental colors of the Army of Tennessee to a new flag, one used by Lee's army in the east. The 7th Florida was issued a Saint Andrews Cross flag, also known as the Army of Northern Virginia pattern flag or the Confederate Battle Flag, which they painted their regimental information on.

In the north, Grant had been promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the United States Army. He assumed this role from the battlefields in Virginia, leaving Sherman in charge of the Military District of the Mississippi, and all armies contained therein.

Prior to Grant’s promotion, the military strategy for the north had been concentrated on taking and keeping key cities and towns. Major battles, such as Gettysburg and Chickamauga, were fought over specific locations that provided a tactical or logistical advantage. Others, such as Manassas and Winchester, were fought to stop an army from advancing on a strategic or otherwise important location. The federal forces in Northern Virginia had spent so much time and lost so many men trying and failing to take Richmond, all the while Lee was growing in popularity to an almost mythical status. Grant saw an error in this method of warfare: if you only attack strategic points, you always allow your enemy to get away, refit, and live to fight another day. Grant believed the capture of Richmond would not be as important as the capture of Lee’s army. Because of this, Grant devised a new strategy for the war: he no longer wanted to attack locations, he wanted to attack Lee. He told Major General George Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.”

Click to enlarge. This just one of dozens maps of the Atlanta Campaign produced by the American Battlefield Trust. To see more, please visit their website.

Grant realized in order to succeed in destroying Lee, he needed to organize a coordinated effort on all fronts. He moved some troops around and ordered attacks on the various Southern armies to prevent them from being able to reinforce Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. For the troops in Georgia and East Tennessee, the result of this was the Atlanta Campaign.

Sherman left the area surrounding Chattanooga for Atlanta in May of 1864. His goal was to eliminate confederate forces in northern Georgia and seize the city of Atlanta. Doing so would slow the movement of troops and supplies around the south, while occupying the attention of the south’s western forces. This, in turn, would hamper Lee from being reinforced or resupplied in Virginia.

While Sherman marched on Atlanta, Johnston tried his best to slow the campaign. In the summer of 1864, a number of battles were fought between Chattanooga and Atlanta. The

7th Florida was involved in several of these, most notably the battle of Resaca. By that time, warfare had changed in the western theater. It was less common to see long lines of men standing in fields firing at one another from close distance, and more common to see attackers advance against an entrenched or fortified defender. The 7th Florida experienced that of the defender in the aforementioned scenario. They dug trenches and fortified themselves against the advancing Union forces. Defending a railroad line and junction, the southern forces entrenched themselves on a 4-mile-long line, occupying the high ground and overlooking a creek along most of their line. They were anchored on both ends by creeks, preventing Sherman from flanking them. Over two days on May 14th and 15th, 1864, the two armies fought to a stalemate. Neither side gained or lost any significant ground. Unfortunately for the south, Sherman had ordered a corps to get around the left flank of Johnston. After crossing a creek and marching south, the federals succeeded in their goal. Realizing he had been flanked, Johnston was forced to withdraw.

As Sherman drew nearer to Atlanta, Confederate President Jefferson Davis grew frustrated with Johnston’s inability to stop Sherman’s advance. Johnston had come under harsh criticism for constantly retreating, even after engagements which he had seemingly won. On July 17, 1864, President Davis replaced Johnston with Major General John Bell Hood, who had become a friend of his. At the age of 33, Hood was the youngest man on either side of the war to command an army.

Hood took command of the 50,000 men of the Army of Tennessee as portions of Sherman’s army equaling approximately 80,000 men descended upon Atlanta. Several engagements occurred, during which Hood allegedly came closer to stopping Sherman’s advance than Johnston ever got at any other point during the campaign.

The first of these engagements took place on July 22, 1864 at Peach Tree Creek, where the 7th Florida, now part of the Florida Brigade in Bate’s Division of Hardee’s Corps, was assigned to the right flank. Bate was not heavily involved in the fighting, and the 7th Florida suffered few casualties as a result.

Two days later, Hood attacked a portion of Sherman’s army under McPherson five miles west of Atlanta. Hardee, who had a late start getting to the field, opened the fighting by ordering Bate to attack the rear of the Union defenses,

Artists depiction of the fighting during the Battle of Atlanta

hoping to capture their supply wagons and hospital tents. Bate unexpectedly came across Sweeny’s Division, who repulsed the attack. The rest of the battle was much of the same. While Hood ordered attacks all along the Union line, his subordinates were unable to attack in a coordinated manner, resulting in every advance being repulsed. During the battle, General McPherson was mortally wounded, a great loss for Sherman.

Not long after losing both of these battles, Hood retreated into his defenses around the city of Atlanta. Much like Grant often did, Sherman decided to lay siege to the city instead of attacking it. Throughout most of August, Sherman slowly encircled the city, cutting Hood's supply lines.

The final proverbial nail in the coffin occurred at Jonesboro on August 30 and 31, 1864. Hood sent Hardee and two corps, the 7th Florida likely included, to stop Sherman from destroying his final railroad line into the city. Hardee was easily repulsed, and hood Hood was forced to abandon Atlanta on the evening of September 1, 1864. As he marched out, many of the city's citizens fled with the army. The next morning, Federal troops marched into the city to discover much of the supplies, ammunition, and railroad infrastructure in the city had had been burned or destroyed by feeling rebels, in an attempt to prevent the supplies from falling into Union hands.

Destruction of Hood's ammunition train and depot

Even though the Union army substantially outnumbered the Confederate forces, sometimes almost by a factor of three to one, casualties during the Atlanta Campaign were considerably lower throughout most of the battles. The Battle of Atlanta, which was the bloodiest of the battles during the campaign, had a combined 9,222 casualties out of the estimated 75,301 engaged. Resaca had a combined 5,547 casualties out of the 158,787 total engaged. By comparison, Chickamauga had about 125,000 engaged, 34,264 of which became casualties. This drastic change can be attributed to the change in tactics and the greater use of fortifications and entrenchments throughout the campaign.

Tennessee Campaign

After losing Atlanta, Hood moved the Army of Tennessee back to Tennessee. His goal was to threaten Sherman’s supply lines and draw him back to Tennessee in pursuit of Hood. Sherman instead set off on his “March to the Sea,” planning to sustain his army entirely off foraging for provisions in the Georgia countryside. Sherman did, however, dispatch the Army of the Ohio, under Maj. General Schofield, to reinforce Maj. General Thomas’s 25,000 men stationed in Nashville. Sherman hoped Thomas would arrive in Nashville before Hood, and the combined armies would outnumber the Confederates.

After spending some time to consolidate and reinforce his army, Hood advanced into Tennessee in September of 1864. At that time, he had approximately 38,000 men. The armies of Hood and Schofield would soon clash at Franklin, Tennessee, on November 30, 1864. Schofield quickly erected defenses focusing on the south side of the town, which was the direction of Hood’s advance. Again, Hood placed Bate and the Florida Brigade on his flank, this time his left. Hood advanced his center and right, pushing the Federals out of

Click to enlarge. This map depicts the battle of Franklin, TN

their advanced defenses. As Hood approached the main Union line, he ordered a charge across much of his line. As his center and right fell back to reform and advance again at least six times, the left was held back. It was not until close to nightfall the Bate on the left was sent in. Hood’s attack was repulsed along the entire line. This attack became known as the “Pickett’s Charge of the West.” The Confederates suffered heavy casualties, with Hood losing nearly 20% of his army, including six generals and eight additional top commanders.

While the Union ceded the field soon after the battle, Schofield succeeded in holding Hood back until he could repair the bridges between Franklin and Nashville, allowing him to reach Thomas’s army before Hood could stop him.

The Army of Tennessee was decimated, but they continued to pursue Schofield all the way to Nashville. When he faced Schofield and Thomas’s combined armies on December 15 and 16, 1864, Hood was outnumbered two to one. With only 30,000 men, Hood ambitiously attempted to take the city, but he was decisively defeated. The 7th Florida did not partake heavily in the fighting for this battle.

Hood’s Tennessee Campaign cost his army over 23,000 casualties. The Army of Tennessee was virtually non-existent, and retreated into Mississippi. Hood resigned his command in January 1865, what was left of the Army of Tennessee was transferred to the Carolinas to join General Johnston’s opposition of Sherman’s march north.

Surrender

The 7th Florida, still part of the Florida Brigade, experienced its last action at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19-21, 1865. They were involved in fighting at several places throughout the battle throughout all three days. There Johnston suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Sherman. This was the last large-scale battle of the war. At Durham Station on April 26th, 1865, Johnson formally surrendered what remained of his army, including the 7th Florida, to Sherman.

The 7th Florida, a regiment consisting of nearly 1000 men when formed, ended the war with less than 200. As with every regiment in the war, more casualties came from sickness and disease, not battle, though they suffered their share of battle losses. Company K also suffered heavy losses, though a majority was not due to battles or sickness, but transfer. Many of the men who were originally in the company when it was known as the Key West Avengers, along with several of those who enlisted as infantrymen, transferred to the Confederate Navy or Coast guard. They had initially signed up to be in the coast guard, not the infantry, and were unhappy with the life of an infantry soldier. Major Mulrenan was one of these men.

Sources for this article include the following:

Mr. M. J. Sterman

American Battlefield Trust

U. S. National Park Service

The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant

Advance and Retreat, the Personal Memoirs of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood

All images courtesy of the following:

Mr. M. J. Sterman

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Project

National Archives

All maps courtesy of the following:

American Battlefield Trust