7th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry

Company K

Formation & Early War

The 7th New Hampshire was mustered at Manchester, New Hampshire, on December 13, 1861. At its inception, the regiment had nearly 1,000 men, as was standard for regiments on both sides during the war. Its men came from southeast New Hampshire, with Company K recruiting its members from at least Hillsborough County and Strafford County. It was originally commanded by Col. Haldimand S. Putnam.

The 7th New Hampshire was quickly assigned to the Department of Florida. On February 12, 1862, they were ordered to report to the Dry Tortugas, where they remained until June 16, 1862. While in the Dry Tortugas, they were under the command of Brigadier General John Milton Brannan. Their time in garrison at the Dry Tortugas was uneventful.

They were briefly assigned to South Carolina from June to September 1862, but were again sent to Florida. It is possible the 7th New Hampshire was involved in the attack on the St. John's Bluff, overlooking the St. John's River. During this fight, Gen. Brannan, commanding several infantry regiments, worked with the navy to drive confederate artillery forces from a rudimentary fort overlooking the river. This was of strategic importance, as

Col. H. S. Putnam, 7th N. H.

controlling the river allowed the Union forces to raid farms, ranches, and towns on the interior of North Florida.

Fort Wagner

On June 15, 1863, the 7th New Hampshire was again sent to South Carolina, this time to join the X corps in support of the federal attempt to occupy Charleston - the place the rebellion began. While it is arguable occupying Charleston provided little tactical advantage to either side due to the Union blockade and the city's lack of major industry, Charleston was fought over for another reason. The city was seen as a symbol of rebellion and secession in the north, and a symbol of independence in the south.

Brigadier General Quincy Gillmore, commanding the X Corps, was assigned to seize the city. The plan hinged on seizing Fort Sumpter, at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. Fort Sumpter was heavily defended, not only by the fort and its location, but also by additional forts and batteries surrounding Charleston Harbor, making an attack on Fort Sumpter difficult and potentially costly.

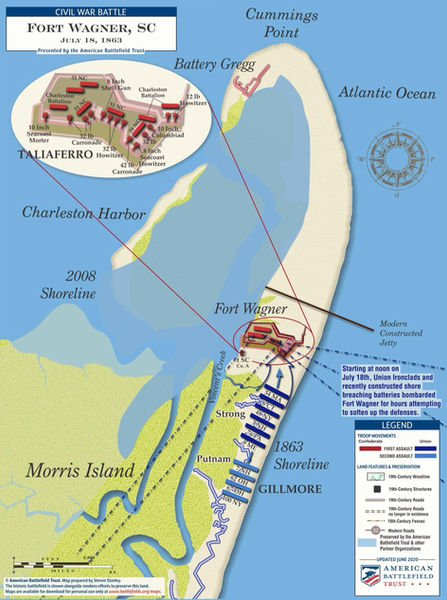

One of these forts was Fort Wagner, located on Morris Island, on the south side of Charleston Harbor. Fort Wagner protected the northern tip of the island, where another battery was located. In order to take Fort Sumpter, and in turn, Charleston, Gillmore planned to assault Fort Wagner, place batteries on the north end of Morris Island, and lay siege to Fort Sumpter.

After initial failed assaults in early July, Gillmore ordered a heavy ground and naval bombardment of Fort Wagner. On July 18, 1863, some 5,000 infantry advanced north across the beaches to assault the roughly 1,600 confederate forces within the fort. The first infantry assault was led by the famed 54th Massachusetts, and the second was led by the 7th New Hampshire. During this assault, Col. Putnam commanded the brigade his regiment was in. He was shot through the head while attempting to enter the fort, and died instantly. His body was never recovered.

The July 18 assault on Fort Wagner would prove to be a costly failure. Of the 5,000 federal troops who advanced on the fort, 1,515 fell, including several Colonels. The 7th New Hampshire entered the battle with 505 men, and they lost 77 killed, captured, or wounded. Only 174 Confederate defenders became casualties.

Click to enlarge. Map of Morris Island and attack on Fort Wagner.

For the 7th New Hampshire, the attempt to take Charleston was not over. Gillmore laid siege to Fort Wagner, and after 60 days the fort was abandoned by the south on September 7. Morris Island was finally in federal hands, and the siege on Fort Sumpter began. Unfortunately, Fort Sumpter would prove much more difficult to capture. Sumpter never fell, and was finally abandoned in 1865 as General Sherman approached Charleston.

Lt. Col. Joseph C. Abbott, who had been the second in command of the 7th New Hampshire since its formation and had immediate command of the regiment at Fort Wagner, was promoted to Colonel and given command of the 7th New Hampshire on July 22, 1863.

Col. J. C. Abbott, 7th N. H.

Olustee (Ocean Pond)

In February, 1864, the 7th New Hampshire was again sent to Florida, where they were assigned to the Department of Florida under General Seymore.

That winter, the 7th New Hampshire and the 7th Connecticut, regiments serving in the same division, both were given the new Spencer Repeating Rifle, with a capacity of seven rounds. This greatly increased the effectivness and battlefield value of these regiments. Though they remained separate regiments, the 7th N. H. and the 7th Conn. became known as the "77th New England."

The move to Florida, which included the "77th New England" and the 54th Massachusets, was ordered by Gillmore in response to Lincoln's orders to establish a Union friendly government in Florida. It had additional goals, as well. The Federals also hoped to sever confederate supply routs and recruit African American soldiers.

After quickly landing and seizing Jacksonville on February 5 and 6, Seymore began raiding the interior of Florida. He captured a number of confederate camps, troops, and artillery pieces. In response to this, the south dispatched troops from General P. G. T. Beaureguard's command in Georgia to reinforce the roughly 1,500 infantry under General Finegan. With the reinforcements from Georgia, Finegan's forces numbered around 5,000.

In mid-February, 1864, Seymore began marching west in order to accomplish the aforementioned goals. He did not known Finegan had created a line of defense east of Lake City, near a little town called Olustee. On February 20, 1864, the two equal forces clashed in the largest battle to take place in the state of Florida.

In the days leading up to the Battle of Olustee, several companies in the 7th New Hampshire were forced to exchange their new Spencer Carbines with the Springfield rifles being used by a cavalry regiment, which were largely in poor condition. They also received new recruits and draftees from New Hampshire, which the veterans evidentially thought very little of.

The 7th New Hampshire, who occupied a position on the right side of the Union line, performed poorly in the coming battle. A combination of confusing orders, new recruits and draftees, and poor weaponry resulted in the 7th collapsing early in the battle and fleeing to the rear. Col. Abbott was able to rally some of his men, but it did not prove enough to prevent the rebel forces from turning the Union flank.

Battle of Olustee

HDQRS. SEVENTH NEW HAMPSHIRE VOLUNTEERS

Jacksonville, Fla., February 27, 1864

COLONEL: I have the honor respectfully to submit the following report of the part which my regiment took in the engagement near Olustee on the 20th instant: The regiment formed at daylight of the 20th, and, constituting the right of Hawley's brigade, advanced from Barber's plantation, on the road toward Sanderson. The head of the column passed Sanderson about 12 m., and when about 3 miles beyond that place the first picket firing was heard between our skirmishers and those of the enemy. The enemy's skirmishers retired, and the column continued to advance for about 3 miles more, when it came upon the main force of the enemy at a point about 3 miles east of Olustee. My regiment was moving by the left flank and remained in that order until we were under the fire of the enemy. The regiment was then brought by company into line and closed in mass. The order was then given by myself to deploy upon the first company and the deployment commenced. At this moment I was informed by yourself that the deployment was not as you intended, and I at once commanded, "Halt; front'." but the fire of the enemy had now become very severe, and in the attempt to bring the regiment again into column confusion ensued, followed by faltering on the part of some of the men, and finally in almost a complete break. About 100 of the regiment remained upon the ground occupied by the column and the remainder fell back a short distance, when with some other officers I succeeded in rallying a part of them, bringing them into something like order, and again advancing. I continued during the engagement to hold a position a little to the right of that on which my column stood when it was ordered to deploy, and opposed as judiciously as I was able to do what appeared to me to be an attempt of the enemy to flank our right. When it was apparent to me that our line was falling back, I gradually withdrew. It is proper to state, perhaps, that becoming separated from the commander of the brigade in the attempt to rally the battalion, I thereafter received no orders until the close of the engagement.

My loss in officers was 1 killed and 7 wounded. George W. Taylor, first lieutenant and acting adjutant, fell late in the action, having been distinguished throughout for coolness and courage, as he is now lamented by all the regiment who esteem a true soldier. My loss in enlisted men was 14 killed and 97 wounded, and my total loss of officers and men in killed, wounded, and missing was 209. A list of casualties is herewith inclosed.

I am, colonel, very respectfully,

JOSEPH C. ABBOTT,

Colonel Seventh New Hampshire Volunteers.

Col. JOSEPH R. HAWLEY,

Seventh Connecticut Volunteers, Comdg. Brigade.

As stated in Col. Abbott's report above, the 7th New Hampshire lost 209 killed, captured, or wounded. Many of the Union soldiers captured at Olustee were sent to Andersonville Prison, where several died. There were members of the 7th New Hampshire among them.

Petersburg Campaign

In March of 1864, President Lincoln promoted Major General Ulysses S. Grant to Lieutenant General, a rank which had last been held by George Washington, and one Lincoln had to convince congress to reinstate. Along with the promotion, Grant was given overall command of all of the US armies. Despite pressure to establish his headquarters in Washington DC, Grant chose to remain in the field, keeping his headquarters close to General Meade, who commanded the Army of the Potomac.

Prior to Grant’s promotion, the military strategy for the north had been concentrated on taking and keeping key cities and towns. Major battles, such as Gettysburg and Chickamauga, were fought over specific locations that provided a tactical or logistical advantage. Others, such as Manassas and Winchester, were fought to stop an army from advancing on a strategic or otherwise important location. The federal forces in Northern Virginia had spent so much time and lost so many men trying and failing to take Richmond, all the while Lee was growing in popularity to an almost mythical status. Grant saw an error in this method of warfare: if you only attack strategic points, you always allow your enemy to get away, refit, and live to fight another day. Grant believed the capture of Richmond would not be as important as the capture of Lee’s army. Because of this, Grant devised a new strategy for the war: he no longer wanted to attack locations, he wanted to attack Lee. He told Major General George Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.”

Lieutenant General U. S. Grant - note the 4 stars on his shoulder boards

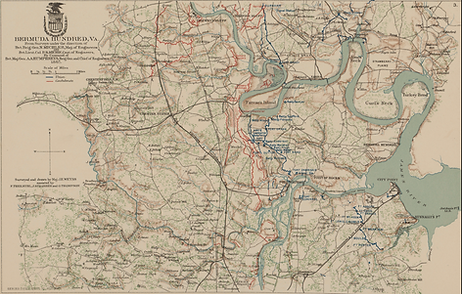

Grant realized in order to succeed in destroying Lee, he needed to organize a coordinated effort on all fronts. He moved some troops around and ordered attacks on the various Southern armies to prevent them from being able to reinforce Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. For the X Corps, the 7th New Hampshire included, that meant they were moving north to Virginia.

Click to Enlarge. Bermuda Hundred Campaign Map.

They arrived in Virginia on April 4, 1864, in time to help secure Bermuda Hundred and City Point. In doing so, they fought at several in battles in quick succession. Swift Creek on May 9, Chester Station on May 10, Fort Darling from May 12 to 14, Drewey's Bluff on may 14 through 16, and Bermuda Hundred from May 16 to August 13.

From there, the 7th New Hampshire, now assigned to the Army of the James, set its sights on Petersburg. Lee's army was

entrenched around Petersburg in order to protect the major railway hub supplying Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. Grant sought to destroy Lee, and massed a far larger army, outnumbering Lee approximately 112,000 to 50,000.

The 7th New Hampshire was involved in the first attack on the city on June 9, 1864. The attack was not successful, and a subsequent attack began on June 15, but the 7th New Hampshire was otherwise engaged at Port Walthal at that time, in an effort to support the second attack on Petersburg. On June 16, the 7th went back to Petersburg to participate in the lengthy siege imposed on the city. They were constantly moved out of the trenches for other attacks. Those include Deep Bottom on August 14 and 15, Chaffin's Farm (New Market Heights) on September 25 through 30, Darbytown and Newmarket Roads on October 7, Darbytown and Charles City Cross Roads on October 13, Fair Oaks on October 27 and 28, and finally, they were assigned to the trenches in front of Richmond near the James River.

The election of 1864 brought some respite from the trenches and battles of the Petersburg Campaign. The regiment was briefly transferred back north to post guard mount during the presidential election. Between November 2 and 17, they were stationed in New York City and Staten Island. Following this, they were reassigned back to the area of the James River in front of Richmond, where they had spent much of the year. They remained there through the new year.

In the nine months of 1864 they spent in Virginia, they fought in no less than 15 different battles, and were in the trenches in front of Petersburg and Richmond for several months. At least four members of the 7th New Hampshire were eventually awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for gallantry during the siege of Petersburg. These men were:

-

Sergeant (Later First Lieutenant) Henry F. W. Little, Company D, awarded for gallantry on the skirmish line near Richmond, September 1864

-

Sergeant (Later First Lieutenant) George Frank Robie, Company D, awarded for awarded for gallantry on the skirmish line near Richmond, September 1864

-

Sergeant (Later First Sergeant) George P. Dow, Company C, awarded for gallantry while in command of his company during a reconnaissance toward Richmond, October 1864

-

Sergeant William Tilton, Company C, awarded for gallant conduct in the field during the Richmond Campaign, 1864

First Lieutenant George P. Dow, courtesy of National Medal of Honor Museum

First Lieutenant Henry F. W. Little, courtesy of National Medal of Honor Museum

Wilmington Campaign

1865 brought the 7th south, to Abbott’s Brigade of the Terry’s Corps in North Carolina. They were immediately involved in the capture of Fort Fisher in January 15th. Fort Fisher, which guarded the Confederacy’s last open port - Wilmington, North Carolina - was nicknamed “the Gibraltar of the Confederacy,” due to its strategic location guarding the Cape Fear River, which was the only access point to Wilmington. Grant attempted to take Fort Fisher in December of 1864 in what can only be described as a debacle by the Union Navy. Refusing to let that happen again, Grant assigned the famed Rear Admiral David Porter (of Forts Henry & Donaldson and Vicksburg) to command the naval attack. With 10,000 infantry under General Terry and 58 Ships under Admiral Porter, the 1,900 confederates garrisoned in the fort were far outnumbered and outmatched.

The navy began their relentless bombardment on the 13th, and on the 15th, a ground assault involving infantry, US Colored Troops, and Marines attacked the fort from the beaches to its north. Abbott’s Brigade, the 7th New Hampshire included, were amongst the troops who entered the fort in the third and final wave of the attack. As the rebels fled the fort, Abbott’s brigade and the USCT pursued them a mile south, further into the peninsula, forcing their surrender. The capture of Fort Fischer effectively sealed the last major stronghold for confederate blockade runners on the Atlantic coast.

The 7th NH subsequently saw action at Half Moon Battery on January 19, Sugar Loaf Battery on February 11, and Fort Anderson on February 15. With Abbott’s Brigade, they marched into Wilmington on February 22, and pursued the retreating confederate column nine miles north of the city to Northeast Station. The pursuit ended when the

.jpg)

Click to Enlarge. Second Fort Fisher Battle Map.

retreating southerners burned the railroad bridge, effectively cutting themselves from Abbott’s Brigade.

That concluded the 7th New Hampshire’s combat experience during the war. They remained on duty in Wilmington until July, 1865, when they were mustered out of service.

Throughout the roughly three dozen battles and engagements across multiple theaters of war, the 7th New Hampshire faired well. They lost 15 Officers and 169 Enlisted killed in battle, and 1 Officer and 241 Enlisted died due to disease. Out of the almost 1,000 who left New Hampshire three and a half years earlier, an estimated 574 returned home, roughly half their regiment.

Sources for this article include the following:

American Battlefield Trust

U. S. National Park Service

National Medal of Honor Museum

The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant

All images courtesy of the following:

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Project

National Archives

National Medal of Honor Museum

All maps courtesy of the following:

American Battlefield Trust

The Petersburg Campaign